Multiplicative Effects of Lipoprotein(a)

- High lipoprotein(a) ((Lp(a)) level is a putative independent risk factor for premature heart attack and stroke.1 The Framingham Offspring Study and several systematic reviews support a 2-fold risk of CAD (coronary artery disease) in people with elevated levels in the absence of any other risk factors.2-4

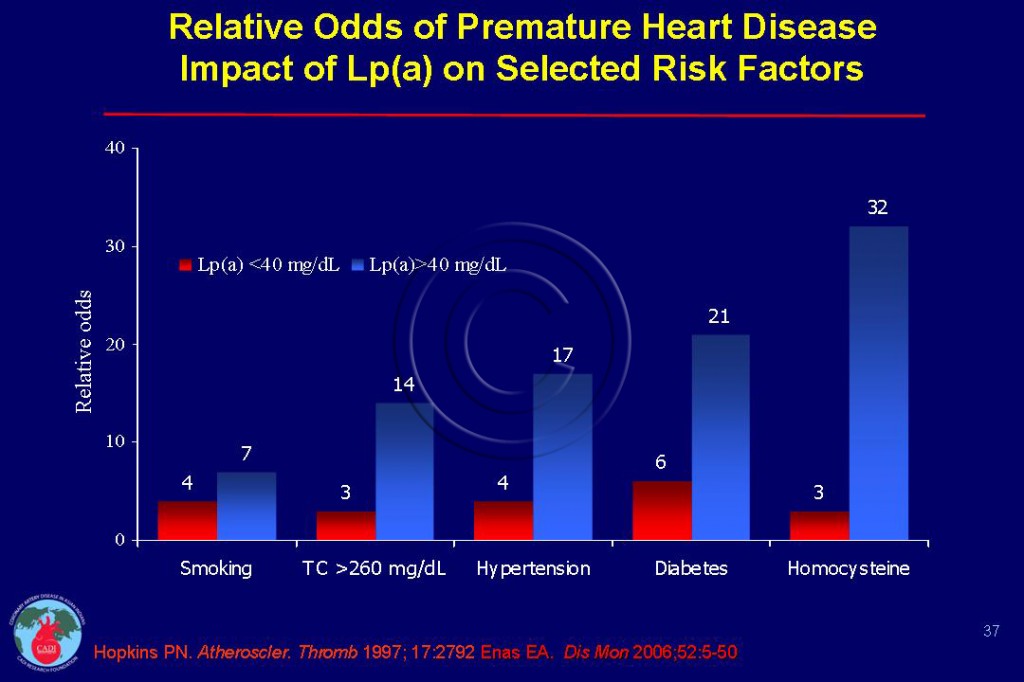

- More recent studies, however, have highlighted the important role of Lp(a) in accentuating the risk associated with virtually all conventional and emerging risk factors (Figure 037).5

- The multiplicative effects of excess Lp(a) on CAD risk with other risk factors suggest a need for a change from the conventional practice of measuring Lp(a) only in those individuals who have none or few other risk factors.5-10

- In the Framingham Heart Study, the adverse effect of Lp(a) was particularly daunting in patients with low HDL-C with some studies showing an 8-fold increase in CVD (cardiovascular disease) risk.6, 11-13 Angiographic studies have shown 7-fold increase in the progression of atherosclerosis in patients with high Lp(a) and low HDL-C.12 This combination appears to be particularly important among Asian Indians who have both high Lp(a) and low HDL levels.14

- The risk of CAD is increased 3-4 fold with either high LDL or high Lp(a) but increases 12 to 14-fold among those with concomitant elevations of both Lp(a) and LDL-C. 5, 15-22

- High TC/HDL-C ratio (which is another powerful predictor of CAD risk) when combined with a high Lp(a) level, increases CAD risk exponentially to 25-fold.5, 7, 12, 13, 20, 23-25 In the INTERHEART Study, Asian Indians had the highest TC/HDL ratio (5.7) and blacks had the lowest (3.9).26

- High triglycerides that produce small dense LDL particles also lead to small, dense Lp(a) and small dense HDL particles, further increasing the atherogenicity of these lipoproteins.1 The risk from Lp(a) may also be increased by high triglyceride levels by this mechanism.1

- High triglyceride levels are associated with lower Lp(a) levels in some studies.27, 28 Conversely, decreasing elevated triglycerides with fibrate therapy may increase Lp(a) levels.29

- The risk amplification of Lp(a) is not limited to various lipoproteins. Several traditional risk factors are known to magnify the risk as well.1 In patients with high blood pressure, Lp(a) excess is a determinant of poor outcome and target organ damage.8, 30

- The CAD risk is increased 12- to 30-fold with concomitant elevations in Lp(a) and homocysteine.5, 31, 32 Homocysteine increases the affinity of Lp(a) to plasmin modified fibrin 20 fold.5, 33 Other studies have shown synergistic adverse effects of Lp(a) with fibrinogen and the apolipoprotein epsilon 4 (apo ε4) allele.34, 35

- High Lp(a) levels increase the risk of CAD associated with other risk factors by a factor of 2 to 10. 5 More importantly, subjects with high levels of Lp(a), homocysteine and high TC/HDL ratio have a 122-fold risk of CAD if any one of the conventional risk factors is also present.1 Certainly, the presence of additional risk factors can further double or triple the risk from Lp(a).36 For comparison, the CAD risk is only 20-fold in patients with all five major risk factors combined.37

- These multiplicative effects of conventional and emerging risk factors appear to provide a plausible explanation for the excess burden of CAD among Asian Indians.1

Sources

1. Enas EA, Chacko V, Senthilkumar A, Puthumana N, Mohan V. Elevated lipoprotein(a)–a genetic risk factor for premature vascular disease in people with and without standard risk factors: a review. Dis Mon. Jan 2006;52(1):5-50.

2. Erqou S., Kaptoge S, Perry PL, et al. Lipoprotein(a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. JAMA. Jul 22 2009;302(4):412-423.

3. Hopewell JC, Clarke R, Parish S, et al. Lipoprotein(a) genetic variants associated with coronary and peripheral vascular disease but not with stroke risk in the Heart Protection Study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. Feb 1 2011;4(1):68-73.

4. Genser B, Dias KC, Siekmeier R, Stojakovic T, Grammer T, Maerz W. Lipoprotein (a) and risk of cardiovascular disease–a systematic review and meta analysis of prospective studies. Clin Lab. 2011;57(3-4):143-156.

5. Hopkins PN, Wu LL, Hunt SC, James BC, Vincent GM, Williams RR. Lipoprotein(a) interactions with lipid and nonlipid risk factors in early familial coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17(11):2783-2792.

6. von Eckardstein A, Schulte H, Cullen P, Assmann G. Lipoprotein(a) further increases the risk of coronary events in men with high global cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(2):434-439.

7. Solymoss BC, Marcil M, Wesolowska E, Gilfix BM, Lesperance J, Campeau L. Relation of coronary artery disease in women 60 years of age to the combined elevation of serum lipoprotein (a) and total cholesterol to high-density cholesterol ratio. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72(17):1215-1219.

8. Sechi LA, Kronenberg F, De Carli S, et al. Association of serum lipoprotein(a) levels and apolipoprotein(a) size polymorphism with target-organ damage in arterial hypertension. Jama. 1997;277(21):1689-1695.

9. Agewall S, Fagerberg B. Lipoprotein(a) was an independent predictor for major coronary events in treated hypertensive men. Clin Cardiol. 2002;25(6):287-290.

10. Gazzaruso C, Garzaniti A, Falcone C, Geroldi D, Finardi G, Fratino P. Association of lipoprotein(a) levels and apolipoprotein(a) phenotypes with coronary artery disease in Type 2 diabetic patients and in non- diabetic subjects. Diabet Med. 2001;18(7):589-594.

11. Bostom AG, Gagnon DR, Cupples LA, et al. A prospective investigation of elevated lipoprotein (a) detected by electrophoresis and cardiovascular disease in women:The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1994;90(4):1688-1695.

12. Cobbaert C, Jukema JW, Zwinderman AH, Withagen AJ, Lindemans J, Bruschke AV. Modulation of lipoprotein(a) atherogenicity by high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in middle-aged men with symptomatic coronary artery disease and normal to moderately elevated serum cholesterol. Regression Growth Evaluation Statin Study (REGRESS) Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30(6):1491-1499.

13. Wang XL, Cranney G, Wilcken DE. Lp(a) and conventional risk profiles predict the severity of coronary stenosis in high-risk hospital-based patients. Aust N Z J Med. 2000;30(3):333-338.

14. Karthikeyan G, Teo KK, Islam S, et al. Lipid profile, plasma apolipoproteins, and risk of a first myocardial infarction among Asians: an analysis from the INTERHEART Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. Jan 20 2009;53(3):244-253.

15. Luc G, Bard JM, Arveiler D, et al. Lipoprotein (a) as a predictor of coronary heart disease: the PRIME Study. Atherosclerosis. 2002;163(2):377-384.

16. Wang XL, Tam C, Mc Credie R, Wilken D. Determinants of severity of coronary artery disease in Australian men and women. Circulation. 1994;89:1974 – 1981.

17. Seed M, Hoppichler F, Reaveley D, et al. Relation of serum lipoprotein(a) concentration and apolipoprotein(a) phenotype to coronary heart disease in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(21):1494-1499.

18. Armstrong VW, Cremer P, Eberle E, et al. The association between serum Lp(a) concentrations and angiographically assessed coronary atherosclerosis. Dependence on serum LDL levels. Atherosclerosis. 1986;62(3):249-257.

19. Maher VMG, Brown BG, Marcovina SM, Hillger LA, Zhao XQ, Albers JJ. Effects of lowering elevated LDL cholesterol on the cardiovascular risk of lipoprotein(a). Jama. 1995;274(22):1771-1774.

20. Schaefer EJ, Lamon-Fava S, Jenner JL, et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of coronary heart disease in men. The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial. Jama. 1994;271(13):999-1003.

21. Cantin B, Gagnon F, Moorjani S, et al. Is lipoprotein(a) an independent risk factor for ischemic heart disease in men? The Quebec Cardiovascular Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31(3):519-525.

22. Rifai N, Ma J, Sacks FM, et al. Apolipoprotein(a) size and lipoprotein(a) concentration and future risk of angina pectoris with evidence of severe coronary atherosclerosis in men: The Physicians’ Health Study. Clin Chem. Aug 2004;50(8):1364-1371.

23. Dahlen GH, Srinivasan SR, Stenlund H, Wattigney WA, Wall S, Berenson GS. The importance of serum lipoprotein (a) as an independent risk factor for premature coronary artery disease in middle-aged black and white women from the United States. J Intern Med. 1998;244(5):417-424.

24. Grover SA, Coupal L, Hu XP. Identifying adults at increased risk of coronary disease. How well do the current cholesterol guidelines work? Jama. Sep 13 1995;274(10):801-806.

25. Stampfer MJ, Sacks FM, Salvini S, Willett WC, Hennekens CH. A prospective study of cholesterol, apolipoproteins, and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(6):373-381.

26. McQueen MJ, Hawken S, Wang X, et al. Lipids, lipoproteins, and apolipoproteins as risk markers of myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): a case-control study. Lancet. Jul 19 2008;372(9634):224-233.

27. Rainwater DL, Ludwig MJ, Haffner SM, VandeBerg JL. Lipid and lipoprotein factors associated with variation in Lp(a) density. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15(3):313-319.

28. Nago N, Kayaba K, Hiraoka J, et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels in the Japanese population: influence of age and sex, and relation to atherosclerotic risk factors. The Jichi Medical School Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141(9):815-821.

29. Ko HS, Kim CJ, Ryu WS. Effect of Fenofibrate on Lipoprotein(a) in Hypertriglyceridemic Patients: Impact of Change in Triglyceride Level and Liver Function. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. Oct 2005;46(4):405-411.

30. Ruiz J, Thillet J, Huby T, et al. Association of elevated lipoprotein(a) levels and coronary heart disease in NIDDM patients. Relationship with apolipoprotein(a) phenotypes. Diabetologia. 1994;37(6):585-591.

31. Foody JM, Milberg JA, Robinson K, Pearce GL, Jacobsen DW, Sprecher DL. Homocysteine and lipoprotein(a) interact to increase CAD risk in young men and women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20(2):493-499.

32. Harpel PC, Zhang X, Borth W. Homocysteine and hemostasis: pathogenic mechanisms predisposing to thrombosis. J Nutr. 1996;126(4 Suppl):1285S-1289S.

33. Harpel PC, Chang VT, Borth W. Homocysteine and other sulfhydryl compounds enhance the binding of lipoprotein(a) to fibrin: a potential biochemical link between thrombosis, atherogenesis, and sulfhydryl compound metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(21):10193-10197.

34. Cantin B, Despres JP, Lamarche B, et al. Association of fibrinogen and lipoprotein(a) as a coronary heart disease risk factor in men (The Quebec Cardiovascular Study). Am J Cardiol. 2002;89(6):662-666.

35. Gerdes LU, Gerdes C, Kervinen K, et al. The apolipoprotein epsilon4 allele determines prognosis and the effect on prognosis of simvastatin in survivors of myocardial infarction : a substudy of the Scandinavian simvastatin survival study. Circulation. 2000;101(12):1366-1371.

36. Enas EA. Avoiding premature coronary deaths in British Asians: Guidelines for pharmacologic intervention are needed. BMJ. 1996;312:376.

37. Enas EA. Lipoprotein(a) and coronary artery disease in young women: A stronger risk factor than diabetes? Circulation. 1998;97:293-295.